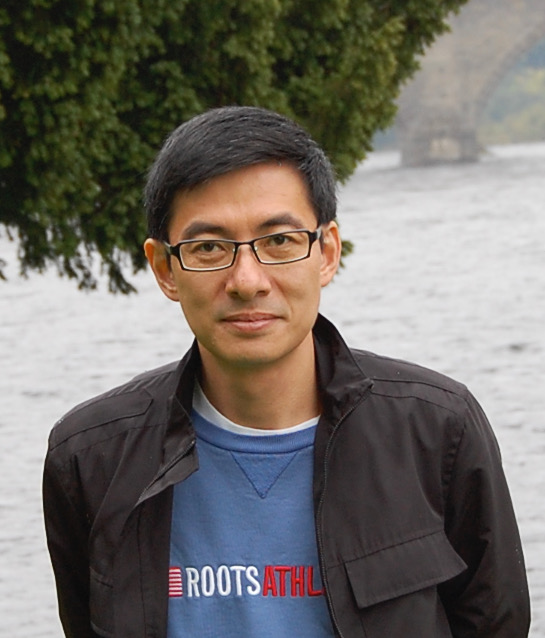

In Conversation with Author Richard Perkins Hsung

HELLO AUTHOR RICHARD PERKINS HSUNG, WELCOME TO WORLDAUTHORS.ORG! CAN YOU BRIEFLY OVERVIEW YOUR MOTHER’S LIFE AND THE INSPIRATION BEHIND HER MEMOIR, SPRING FLOWER?

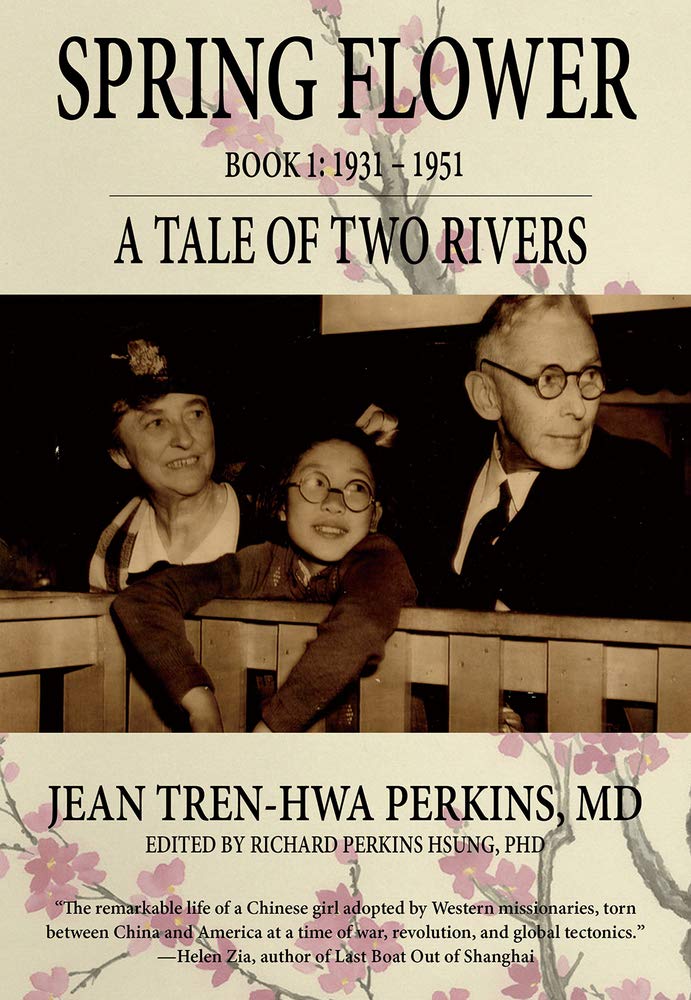

My mother was born into dire poverty in 1931, during the catastrophic Yangtze River flooding that ultimately killed more than 4 million people. When she was a year old, her biological parents gave her up for adoption to an American missionary couple, who had founded a hospital nearby, Dr. Edward C. Perkins and Georgina MacDonald Phillip, and her adoptive parents anglicized her name to Jean Tren-Hwa Perkins. After that, my mother had an idyllic childhood, living in a large house with gardens and servants, and she attended English-speaking schools—first in China; then in Yonkers, New York, during World War Two. On VE-Day 1945, she and her parents set sail for India, where she spent a year at a progressive British boarding school in the Himalayas before returning to China in 1946. After the Communist takeover of China in 1949, my mother’s parents continued working at their hospital, but they had to flee China a year later in the dangerously vitriolic, anti-American atmosphere amidst the Korean Conflict, a proxy war between America and China. My mother was left behind, unable to emigrate to the U.S. until 1980.

In the ensuing thirty years living in China, my mother graduated from medical school and worked as an ophthalmologist while raising two young children. Then came the tumultuous 1966 Cultural Revolution that lasted a decade, and her husband (my father), a world-renowned agronomist, was taken to a labor camp for criticizing the government’s disastrous economic development and agricultural policies that led to a nationwide famine. When my mother finally made it back to America, her cousin, the daughter of Dr. Edward Perkins’ older brother Henry, encouraged her to write a book about her experiences, and that suggestion was reinforced by other Americans and even visiting scholars from China after they heard her stories. My mother hesitated, then gave it a try, focusing on the extraordinary people who supported her emotionally and materially, including those she met during the hellish years in China, when she lived dangerously as someone with an American background.

WHAT MOTIVATED YOU TO COMPLETE YOUR MOTHER’S MEMOIR, AND HOW DID YOU APPROACH THE EDITING AND COMPILATION PROCESS?

My mother began writing her memoir in the early 1980s, but by the early 1990s, her progress ground to a halt. I learned later that the writing had driven her into a dark depression that ultimately devolved into dementia in 1998. When I visited her in January 2014, she’d spent nine years in the same nursing home bed. I began our time together by saying “Happy New Year,” and then I, somewhat boldly, asked her why she was continuing to live and if she wanted to be free and on “the other side.” Of course, she said nothing, as she had been unresponsive for a few years by then. Then, as I was leaving, I blurted out, “Oh, I know why. You’re worried about who will finish your book! Okay, I’ll do it, but only if you promise you’ll leave this world when you feel ready. I want you to be free.” A few months later, she died as if she’d understood my words. I was relieved she was no longer bedridden but wondered how in the world I would be able to fulfill my promise.

Naively, I jumped right in. My mother had already written more than a thousand pages of completed chapters and notes. As a college professor, I always advised my students not to enter the lab unprepared, to study the protocols first, seek advice from those with experience, and read the literature. I didn’t do any of that, and it took me another decade to complete the work. With the help of a great editor, I’ve now finished three volumes of my mother’s memoir, titled Spring Flower, and Earnshaw Books agreed to publish it all.

HOW DID YOUR MOTHER’S EXPERIENCES DURING THE YANGTZE RIVER FLOOD AND BEING ADOPTED BY MEDICAL MISSIONARIES SHAPE HER SENSE OF IDENTITY?

My mother’s first year of life was difficult. Her biological parents were, literally, dirt-poor, and in those days, girls were not valued. But after being adopted by Dr. and Mrs. Perkins, she grew up in comfort, surrounded by Westerners and attending English-language schools in China. She was close with her adoptive mother, Georgina, who was her primary role model. She became whoever Georgina was, and since Georgina was born and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland, before moving to Yonkers, New York, there were times in my mother’s childhood she thought she was a Scot. My mother never met her Scottish maternal grandfather, an architect in New York, who wrote and sent her gifts often. But her maternal grandmother ended up going to Kiukiang in 1941 and eventually died and was buried in a cemetery for foreigners in China. my mother also became close to her Scottish grandmother. During World War II, the family lived in Yonkers (as Japan, an “enemy” of the U.S. occupied their region of China), affirming her sense of being American with American English as her first language. When she was finally able to emigrate to the U.S. in 1980, she felt she was coming home.

But in China, especially after her parents fled, she did not fit in. She was a kind of outsider, never fully understanding her country’s culture and history. With effort, she relearned Chinese well enough to overcome her American accent and pretty much blend in. But it was dangerous in those years to be seen as American, until Nixon opened relations with China in 1972.

In the mid-1980s, when she was finding her way around Boston and seeking U.S. citizenship, China invited her to return “home” and assume important academic and clinical positions. But for her it was too little too late, and my mother told me, “Not over my dead body. America is my home.” Still, sadly, it took 18 years before the U.S. granted her citizenship. So, her identity was a source of inner conflict and pain. She felt herself American, was not accepted in China until after she left, and she never felt welcome in America, despite seeing herself as American.

CAN YOU ELABORATE ON MISSIONARIES’ VITAL BUT MISUNDERSTOOD ROLE IN 20TH-CENTURY CHINA AND HOW IT INFLUENCED YOUR FAMILY’S STORY?

To many around the world, missionaries have a well-earned tarnished reputation. From requiring “Rice Christians” to convert before being fed, clothed, or provided medical care; to disrespecting peoples and cultures; to working closely with those who extracted resources, missionaries have often encouraged people to look skyward while they and others stole their land. I’m not denying these facts, but the work of my American grandparents, Dr. and Mrs. Perkins, represents thousands of missionaries worthy of praise. My mother knew this firsthand, and I learned about when I completed her memoir.

In 1918, my grandparents established a new clinic called “Water of Life Hospital” in a rented facility in Kiukiang, China, In 1931, they spent their own funds to build a three-story, state-of-the-art hospital, and this hospital building remains fully functional today. Together, with Bessie and Deanetta Ploeg, two nurses from Grand Rapids, Michigan, they trained generations of Chinese physicians and nurses and treated tens of thousands of Chinese patients. And, like many other missionaries, they helped raise awareness of human rights, especially women’s rights. Missionaries throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America continue to provide beneficial services in healthcare, human rights, and education, and in my opinion, they deserve our appreciation, despite the misdeeds of too many others.

WHY WAS YOUR MOTHER’S U.S. CITIZENSHIP BLOCKED DESPITE BEING ADOPTED BY AMERICAN MISSIONARIES, AND WHAT OBSTACLES DID SHE ENCOUNTER IN PURSUING CITIZENSHIP?

After settling in Boston in the early 1980s, my mother and I spent hours in the dimly lit rooms of the John F. Kennedy Building in Boston’s Government Center. There were dozens of newcomers to America in the same room, and we would sit or stand nervously and clutch our paper ticket, listening intently for our number to be called. And before it was our turn, we heard frustrated pleading from others petitioning for citizenship. Time after time, we were shouted at, told we’d filled out forms incorrectly, despite following their instructions to a “T.” It took 18 years before my mother was granted citizenship, even though she had already been recognized as a legally adopted daughter of Americans in the U.S. Supreme Court in Shanghai in 1940.

HOW DID THE RISE OF COMMUNISM IN CHINA AFFECT YOUR FAMILY AND THE RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN IT FOR GENERATIONS? CAN YOU DISCUSS SPECIFIC INSTANCES OR STORIES THAT HIGHLIGHT THE DESTRUCTIVE IMPACT OF COMMUNISM ON CHINESE FAMILIES?

When the Communists drove the Republic Nationalists to Taiwan in 1949, Dr. and Mrs. Perkins stayed and kept their hospital in Kiukiang running. These missionaries were highly skilled healthcare providers, which the Chinese desperately needed. But the Korean War—a proxy war between the U.S. and China—turned up the heat on anti-Americanism, and my grandparents were forced to flee China the following year, leaving my mother behind.

At the end of the Korean War, China entered decades of mismanagement with costly policies that led to economic collapse, famine, and authoritarian brutality. Many of these decisions were based on a blind allegiance to the Soviet Union, arrogance toward the West, and an ideological drive to attain Marx’s ideal Communist state overnight. The first of these horrible periods was called the Great Leap Forward, and the manmade famine it created killed millions between 1958 and 1960.

The Great Leap Forward was followed by Mao’s 1966 Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a plot to regain absolute control by blaming others for the 1950s economic failures, leading to imprisoning or killing millions they deemed capitalists. What began as a political purge at the highest levels became a nationwide class struggle pitching have-nots against haves. The country spiraled into anarchy during which tens of millions of teenagers abandoned their classrooms and took the “faux class struggle” to the streets. These ill-informed and adrenaline-driven teenagers became the Red Guards and were praised as guardians of communist ideals, defenders of proletarianism against capitalistic values, and pioneer soldiers of the great revolution. They terrorized the streets, destroying banks, shops, and restaurants, razing temples, churches, and theaters, and burning books because so-called capitalist values included anything related to culture, history, or religion—Chinese or Western.

Knowledge and creativity were also regarded as personal possessions. The anarchy was a smoke screen to regain political power, and silencing the educated was an effective way to suppress dissent. Targeting professionals and intellectuals also served to shift the blame for the country’s failing economy and starving millions of people to death to them. College campuses were closed; even elementary and high schools stopped functioning. The Red Guards marched their teachers and professors onto the streets to be humiliated, tortured, and many were even murdered in broad daylight. My father was a renowned agronomist, and for questioning the government’s economic policies and trying to set a wiser direction based on agricultural realities and not wishful thinking and ideology about rice farming, he was sentenced to a Stalinesque gulag at a prison camp. My mother, with her American and religious background, was also ripe for persecution, but she managed to continue working as a medical doctor, although she was frequently rushed off to the countryside as part of the Revolution’s reform, reeducation, and rustication program.

Then, martial Law was declared, and in an about-face, millions of Red Guards were sent to China’s Siberia for “reform. “After serving the Revolution’s purpose, they became its victims, toiling under the harshest conditions and living in poverty for years. Most never completed high school; a generation was thoroughly destroyed too. By the mid-1970s, every layer of society, even the so-called proletariat, had gone through some form of “cleansing.” Farmers stopped farming, factories stopped producing, and China faced another devastating famine within a decade of the earlier one. Most of us lived through that period on rationed food, salty watered-down food, and clothing stamps. When the Cultural Revolution mercifully ended in 1976, China’s culture, history, art, knowledge, virtue, morals, reverence, and integrity had been decimated.

Over the decades since, China has bravely risen from its ashes. However, despite the bustling economy and glittering skylines, China is still recovering from the trauma and destruction caused by this heinous revolution. Most Chinese people today regard 1978 as the year they were liberated, when China reopened to the world under the leadership of Chairman Premier Hua Guo-Feng, China’s Gorbachev, and later Deng Xiao-Ping. That was the time my mother began the process of returning to America.

HOW DID LANGUAGE AND DISPLACEMENT STRUGGLES CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR MOTHER’S DEPRESSION, AND HOW DID SHE COPE WITH THESE CHALLENGES? HOW DID THESE STRUGGLES SHAPE HER PERSPECTIVE ON IDENTITY AND BELONGING?

My mother experienced three major displacements: (i) Being given up for adoption after the Yangtze River flooding in 1931; (ii) separation from her American parents when they had to flee China in 1950; and (iii) returning to America in 1981 only to face not being accepted. Being an outsider in the U.S., after holding up an idealized image of America to maintain her sanity through decades of strives in China during a time of gross inhumanity, was more than she could handle. When faced with the bureaucratic impertinence many immigrants have faced since the years of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, she struggled make sense of it and wondered where she belonged. Despite this, my mother stubbornly held onto her identity as an American and was convinced that the country she remembered so fondly would soon recognize her. It was an inner conflict she was never able resolve, and although Spring Flower, her memoir, has many beautiful and memorable stories and highlights, the ways this tragedy impacted her identity was arguably harder for her to take than the trauma of living in China.

WHAT SURPRISING OR POIGNANT REVELATIONS ABOUT YOUR MOTHER’S AND YOUR OWN LIFE DID YOU UNCOVER WHILE WORKING ON THE MEMOIR? HOW DID THE PROCESS OF UNCOVERING THESE SECRETS AND TRUTHS SHAPE YOUR PERCEPTION OF YOUR FAMILY’S HISTORY?

Although there were many, I will focus on one. Working on my mother’s book made me recognize the ways my life mimicked hers, not unlike the mirroring concept in chemistry: My mother and I were mirror images of one another. In chemistry, mirror images can be “superimposable” or “non-superimposable.” When two mirror images are superimposable, they are identical or essentially the same. But when they are non-superimposable, the two images are nearly identical but are clearly different entities, like the left and right hand. My mother and I are the non-superimposable kind.

My mother was born during the Yangtze River flood, one of the deadliest natural disasters in the twentieth century, killing four million people. I was born at the onset of the Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a catastrophic, manmade disaster that destroyed generations. My mother was raised by Americans. My sister and I were raised by our loving neighbors in China while my mother worked long hours as an ophthalmologist. When my mother was 14, she was “whisked” from Yonkers’ Hawthorn High School as World War II ended and found herself on a U.S. battleship en route back to Asia. When I was 14, I was yanked out of a junior high classroom in Hangzhou, China, and put on a Japan Airlines flight to Tokyo, and then to America. Neither of our classmates knew what had happened to us. My mother did not want to leave America; I did not want to go to America.

While living in Yonkers, my mother had wanted to be a journalist and an author. Before leaving China, I dreamed about becoming a poet and writer. When my mother returned to China in 1946, she had forgotten Chinese, the language she had to re-learn for the next three decades. When I arrived in the U.S., I hardly spoke a word of English, which put the kibosh on my dream of becoming a writer. And when I made my first pilgrimage back to China in 2000, I, too, had lost my ability to communicate in Chinese, and I knew how she must have felt.

On the day we landed in New York, like my mother before me, the glitter of the city blew me away, and I fell in love with New York, which I sometimes call my first American home. During those first weeks in Manhattan, my mother taught me about baseball, which became my passion. She loved the Yankees, as she’d been to Yankee Stadium with her father in the 1940s. After we settled in Boston, I chose to root for the Red Sox, probably to spite her. But my team was a perennial loser, perhaps not so different from how my mother viewed me, at least it felt that way to me. I could never fulfill her lofty expectations. In 2004, my mother’s first year in the nursing home, we watched the Red Sox play the Yankees, the last time she was sound-minded enough to cheer at fitting moments. That fall, Boston beat her beloved team and lifted the Curse of the Bambino.

So, working on my mother’s life story helped me know myself. I learned about the traumas I carried within me through writing about hers. And I learned about the resilience and strength I have through learning and writing about hers.

HOW DO YOU BELIEVE YOUR MOTHER’S STORY CONTRIBUTES TO A BROADER UNDERSTANDING OF THE CHINESE IMMIGRANT EXPERIENCE, PARTICULARLY FOR WOMEN, AND THE THEMES OF DISPLACEMENT AND HOPE? WHAT MESSAGE OR LESSON WOULD YOU LIKE READERS TO TAKE AWAY FROM SPRING FLOWER AND YOUR FAMILY’S JOURNEY?

There have been three periods of Chinese immigration to the U.S. The first came in the mid-19th century, with most migrants being manual laborers on the West Coast. In the intervening years between the turn of the 20th century and before 1980, Chinese immigrants trickled in predominantly from Taiwan and Hong Kong, constituting a broadly defined second period. My mother was part of that second wave when she lived in Yonkers with her adoptive parents. The third period coincided with my mother’s return to the U.S. in the early 1980s. Upon our arrival, an article in Time magazine commented on a new wave of immigrants. The faces on the cover were refugees from Southeast Asia and China, after the fall of Saigon and when China reopened to the West. By the millennium’s end, the Chinese population in the U.S. had tripled. Today, Chinese Americans are the third largest non-European group in the U.S., and around 30 percent of the Chinese diaspora worldwide live in the U.S.

When humans uproot from their motherland and abandon their mother tongue, it is often because they are fleeing natural or manmade disasters. My mother endured all these extremes, from birth during the Yangtze River flood to a family that could not afford to raise her, to being adopted by kind American missionaries, to living in America during World War II, to surviving a brutal regime in China. After coming back to America, she had a new set of struggles as a single mom raising a son while pursuing a career and, at the same time, seeking to regain her citizenship. I believe my mother’s eighty-three years of struggles and redemption exemplifies the experiences of many immigrants, although hers might have been more dramatic than most.

One takeaway from my mother’s memoir is to never lose hope. Throughout her turbulent life, my mother managed to hang onto a childlike conviction that things would improve. It was hard to convince her otherwise, because even when her inner resources wore thin, there were always people—perhaps they were guardian angels—who came into her life at the exact moment the need was greatest. The essential goodness of her fellow humans always seemed to prevail, even in times of tragedy.